“The neomodernist stranglehold is exemplified by the treatment accorded Fr. Jean Carmignac, who died in 1986. Perhaps the greatest French Bible scholar of the century, who dated the writing of each of the four Gospels between A.D. 40 and 50, he was never allowed to publish

his research, on orders of the French bishops. They accused Carmignac of "an obsession of struggling against the majority of exegetes".”

Paul Likoudis

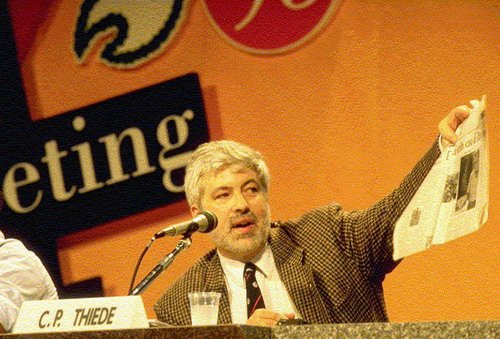

Then came Dr. Carsten Peter Thiede with his dramatic evidence for a radical early dating of the Gospel of Matthew. We read a little of it in the following account:

Christmas Eve 1994 would have come and gone like any other, had it not been for three tiny papyrus fragments discussed in The Times of London’s sensational front-page story. The avalanche of letters to the editor jarred the world into realizing that Matthew d’Ancona’s story was as big as the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The flood of calls received by Dr. Carsten Peter Thiede, the scholar behind the story, and the international controversy that spread like wildfire, give us an inkling as to why the Magdalen Papyrus has embroiled Christianity in a high-stakes tug-of-war over the Bible.

Thiede and d’Ancona boldly tell the story of two scholars a century apart who stumbled on the oldest known remains of the New Testament–hard evidence confirming that St. Matthew’s Gospel is the account of an eyewitness to Jesus. It starts in 1901 when the Reverend Charles B. Huleatt acquires three pieces of a manuscript on the murky antiquities market of Luxor, Egypt. He donates the papyrus fragments to his alma mater, Magdalen College in Oxford, England, where they are kept in a butterfly display case, along with Oscar Wilde’s ring. For nearly a century, visitors hardly notice the Matthew fragments, initially dated to a.d.180-200; but after Dr. Thiede redates them to roughly a.d. 60, people flock to the library wanting to behold a first-century copy of the Gospel.

But what is all the fuss about? How can three ancient papyrus fragments be so significant? How did Thiede arrive at this radical early dating? And what does it mean to the average Christian? Now we have authoritative answers to these pivotal questions. Indeed, the Magdalen Papyrus corroborates the tradition that St. Matthew actually wrote the Gospel bearing his name, that he wrote it within a generation of Jesus’ death, and that the Gospel stories about Jesus are true. Some will vehemently deny Thiede’s claims, others will embrace them, but nobody can ignore Eyewitness to Jesus.

[End of quote]

Paul Likoudis, writing for EWTN in 1997, has more to say on the matter.

I (Damien Mackey) would not necessarily agree with him, though, that “Matthew's is the first Gospel”. Fr. Jean Carmignac (mentioned in this article) made an excellent case for (if I recall correctly) Mark’s being basically the Gospel of St. Peter – and therefore the first gospel - translated by Mark into Greek.

New Book Claims Four Gospels Written Before Fall Of Jerusalem

….

The hundred years' war on the Gospels-led by Rudolf Bultmann, who charged that "we can know practically nothing about Jesus' life and personality," and escalated by some of the most prominent Catholic Bible scholars working today-has produced the intended results of religious indifference, agnosticism, and atheism.

Typical of the Bultmann-inspired Catholic exegetes is Fr. Jerome. Murphy O'Connor, O.P., who, writing in the December, 1996 issue of the Claretians', pontificates that the Gospels are "mythical embellishments," that Jesus didn't know He was God and didn't know where His power came from, that Mary considered Him an embarrassment to the family, that she was not at the foot of the cross as the evangelists relate, and more.

"Do the Gospels Paint a Clear Picture of Jesus?," he asked. Definitely not, he tells his students and readers.

At the core of the dissident biblical exegesis which has produced such disastrous consequences for Catholic life, liturgy, catechetics, and scholarship is a refusal to believe that the Gospels were written by eyewitnesses of the events described.

Though there has been no shortage of genuine Catholic exegetes, archaeologists, and historians who have insisted on an early dating of the Gospels to within a decade or two of Jesus' life, these scholars have often found it difficult to break through the controls put in place by an oppressive neomodernist establishment in both Catholic and Protestant institutions.

(The neomodernist stranglehold is exemplified by the treatment accorded Fr. Jean Carmignac, who died in 1986. Perhaps the greatest French Bible scholar of the century, who dated the writing of each of the four Gospels between A.D. 40 and 50, he was never allowed to publish his research, on orders of the French bishops. They accused Carmignac of "an obsession of struggling against the majority of exegetes.")

Now comes a German scientist, Carsten Peter Thiede, director of the Institute for Basic Epistemological Research in Paderborn, who, with Matthew D'Ancona, is about to dash to pieces the Bultmann-built edifice of modernist exegesis.

Their recently published book, (Doubleday, 1996), is about a small piece of papyrus held at Magdalen College, Oxford, which is the oldest fragment of in existence today.

The fragment contains disjointed segments of 26, but even more important than the writing style, which Thiede pinpointed to the time of Jesus' life, is the use of KS, an abbreviated form of [missing], to refer to Jesus as Lord God- meaning that the ancient author believed that Jesus is divine.

Thiede, a papyrologist, furthermore concludes that must have been the first Gospel written.

The implications of this are enormous. As Thiede and D'Ancona write in their book:

"Bultmann was wrong: The authors of the Gospel could hear far more than the faintest whisper of Jesus' voice.

Indeed, the first readers of may have heard the very words which the Nazarene preacher spoke during his ministry, may have listened to the parables when they were first delivered to the peasant crowd; may even have asked the wise man questions and waited respectfully for answers. The voice they heard was not a whisper but the passionate oratory of a real man of humble origins whose teaching would change the world."

The issue of the dating of the Gospels has implications, furthermore, for believers and nonbelievers alike. "... We have come to realize the extent to which this new claim is directly relevant to the fundamental faith questions which all people, Christian and non-Christian, atheist and agnostic must ask themselves. The redating of the fragments, in other words, has a life beyond the confines of the academy. . .

"The redating of the Gospels- a process which is only now beginning in earnest-may seem an enterprise appropriate to its times, to the mood of the millennium's end. There is now good reason to suppose that the [missing], with its detailed accounts of the Sermon on the Mount and the Great Commission, was written not long after the crucifixion and certainly before the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70; that the was distributed early enough to reach Qumran; that the belonged to the first generation of Christian codices; and that internal evidence suggests a date before A.D. 70 even for the nonsynoptic .... These are the first stirrings of a major process of scholarly reappraisal."

International Upheaval

Thiede's findings are causing an international upheaval among Bible scholars, particularly Catholic exegetes who have bought the Bultmann line that separates the Gospels to a generation or more from Jesus' contemporaries (making them the unreliable voice of an uncertain community) ….

Two hundred years ago, one of the leaders of the Enlightenment, Reimarus, described the task of Church-haters to be to "completely separate what the Apostles presented in their writings (i.e., the Gospels) from what Jesus himself actually said and taught during his lifetime."

….

Footnote

Among the brief sections of the Gospel on the Magdalen fragment is: "Then one of the XII, who was called Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priest and said, 'What will you give me for my work?'"

….