Horrible Histories: Retracting Romans

Part Two:

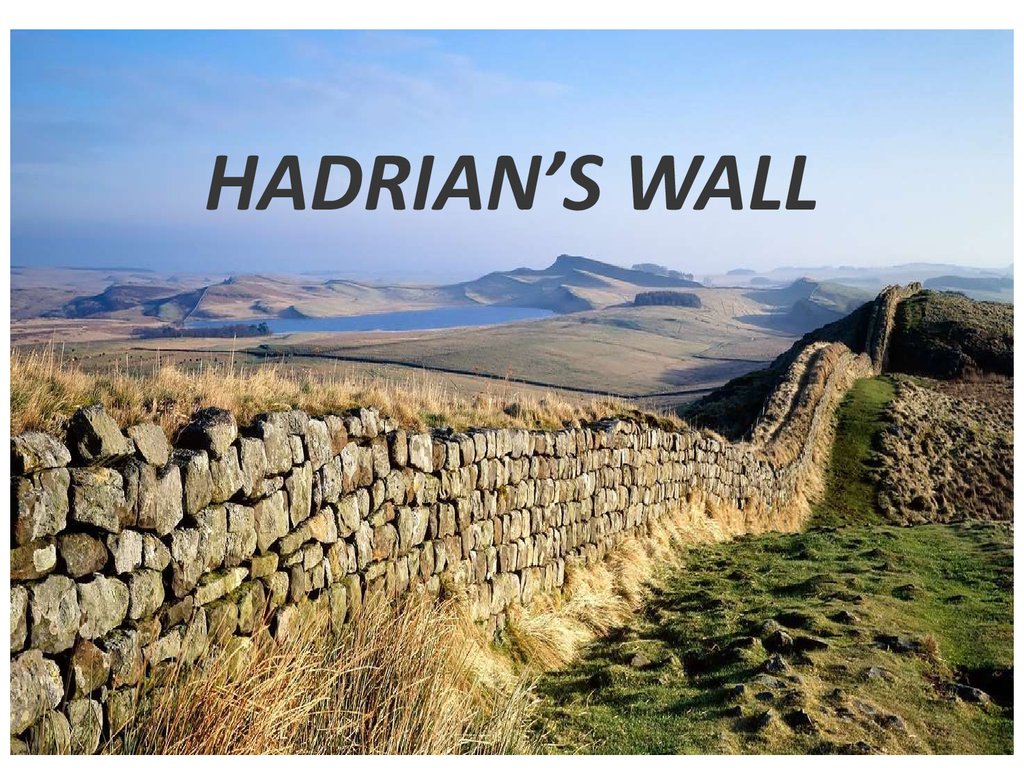

A new interpretation of “Hadrian’s Wall”

by

Damien F. Mackey

“Without Clayton’s work, Hadrian’s Wall today would look more like Offa’s

Dyke”.

Mary Beard

Introduction

Neither the Roman Republicans nor some of the early Roman Emperors have

fared very well in this present series, and in my multi-part:

Famous Roman Republicans beginning to loom as spectral.

Part One: Still a Republic at time of Herod 'the Great'

culminating in:

in which collection of articles famous Roman Republicans, and at least

the emperor Hadrian, are shown to have their origins and proper identities in

Hellenistic rulers.

Hadrian himself has been merged with the Seleucid king, Antiochus IV

‘Epiphanes’, and with Herod ‘the Great’. Archaeologists, as we have found, have

the greatest difficulty in distinguishing the building works of Herod from

those of Hadrian.

Now, in the following intriguing article, Mary Beard has something reached

some unexpected conclusions about the famous, so-called: Hadrian’s Wall:

Was

Hadrian’s Wall built in the nineteenth century?

I am at a conference this weekend. It’s called From Plunder to Preservation and it’s organised by our Victorian Studies Group. In fact right now I should be at the conference dinner, but I begged off. It was bound, I thought, to be a Bacchanalian affair — and, as I am not drinking, I feared that I would either get irritated at everyone else’s jollity or else too tempted to have a glass myself. So I came home to write a review, which I’ve half finished now.

The

idea of the conference is to explore the relationship between heritage and

empire. There hasn’t been a duff paper so far and there are too many highlights

to go through them all. I particularly enjoyed Maya

Jasanoff, who raised the issue of how far (or not) we ought to see

the human plunder of empire, in the form of slaves, as analogous to the plunder

in the form of art works. (In the course of this she talked interestingly about

slave trade tourism in Ghana, and the different treatment of the monuments of

the slave trade between Ghana and Sierra Leone).

On

the classical/Greek side, the husband talked about the Anglican cathedral in Khartoum, designed by Robert Weir Schultz, an Arts and Crafts architect who

had started his career drawing and recording Byzantine monuments in Greece (the

Khartoum church is based on the church of St Demetrius in Thessaloniki). This

paper fitted extraordinarily well with Simon Goldhill‘s on the work of another Arts

and Crafts-man, C. R. Ashbee in Jerusalem. Meanwhile Ed Richardson

had spoken of the classical presentation of the Crimean War (with warships

called things like "Agamemnon").

I

looked instead at Roman Britain. The aim of my talk was to knock a nail into

the coffin of the fashionable view that Roman British archaeology in the

nineteenth century was a handmaiden of empire, that it was practised by

classically trained public schoolboys, imbued with the spirit of empire.

Archaeology was, in other words, imperialism pursued by other means. For

Hadrian’s Wall, read the North West frontier and vice versa.

My

line is that this is a politically correct, but unthinking, approach to the

study of Roman Britain in the nineteenth century. In short, it’s wrong.

What

exactly is the matter with it?

In part,

the supposed imperialist character of Romano-British archaeology is based on selective

quotation. Of course, you can find a whole range of examples where

nineteenth-century archaeologists use comparisons with the British empire, and

laid end-to-end these look pretty impressive. But if you read the original

material itself, there’s really not that much of it and it’s not the driving

force behind the archaeological interpretation. If anything, they are much more

aggressively interested in the role of Christianity in the province.

More

important though is the role of classical texts. There’s a common view that

these classically trained archaeologists had somehow inherited an imperialist

view of their subject from the classical texts they had read. That would, of

course, be possible if those texts really were straightforwardly imperialist in

outlook. But in fact Roman writers expressed deep ambivalence about the effects

of the empire, and correlated Roman moral decline with the expansion of its

imperial territory. More to the point, Tacitus’

Agricola — the key literary text for

understanding Roman Britain — is also the text in which that ambivalence is

expressed most clearly (this is the "make a desert and call it peace"

text). Anyone brought up on the Agricola

would be encouraged to take a wry, not an enthusiastic, position on imperialist

endeavours.

Another

factor is the striking mismatch territorially between the British and Roman

empire. Until the final dismemberment of the Ottoman empire, there was hardly

any overlap between the two (Cyprus, Malta, Gibraltar). This meant that British

archaeology was quite unlike its French equivalent, in the French colonies of

North Africa — where Roman archaeology really did go hand in hand with imperial

expansion. There was no such thing in the nineteenth century as Roman

archaeology in the British empire.

Except,

of course, in Britain itself. Indeed the paradox at the heart of Roman Britain

for its nineteenth-century practitioners was just that: the province which had

been the most distant in the ancient empire, was the metropolis of the modern.

Was Britain centre or periphery?

In

the course of this I looked at Hadrian’s Wall and its Victorian history. Two

men were clearly crucial in its rediscovery (patriotic northerners, and hardly

part of the British imperial project). First there was John

Collingwood Bruce, who conducted ‘pilgrimages’ to the Wall and wrote

the standard guide books. Second was John

Clayton, who preserved miles of the central section of the Wall from

‘native" depredation (in fact he bought up a lot of it to keep it safe).

The

more I read, though, the more I came to realise that Clayton’s interventions

were considerably more significant than simply preservation. Over miles and

miles, Clayton had his labourers rebuild the Wall and in the process he created

for us those all the most impressive sections that tourists now love — several

courses of dry stone masonry, topped with turf, scaling windy ridges. Without

Clayton’s work, Hadrian’s Wall today would look more like Offa’s Dyke.

Another

‘ancient’ monument built by the Victorians then. There’s hardly any that

weren’t, it sometimes seems. ….

No comments:

Post a Comment